The Colonial Press published The World’s Greatest Classics in 1900. Unfortunately, the book series only had 1,000 sets published for universities, and my copy of the Persian Shah Nameh was marked #81 of the set. I obtained this copy of the Persian classics in a random meeting.

My Personal Experience

I have perused the Shah Nameh numerous times, usually looking for a specific story or subject. Yet my first Shahnameh was left in a suitcase when I left the Middle East to go home to get married. I thought I would return soon enough and claim it. Unfortunately, a return for the bag never happened as my new wife and I moved to Central Asia, so others most likely claimed this first copy. Other times like most of you, I just googled the writing and found what I wanted.

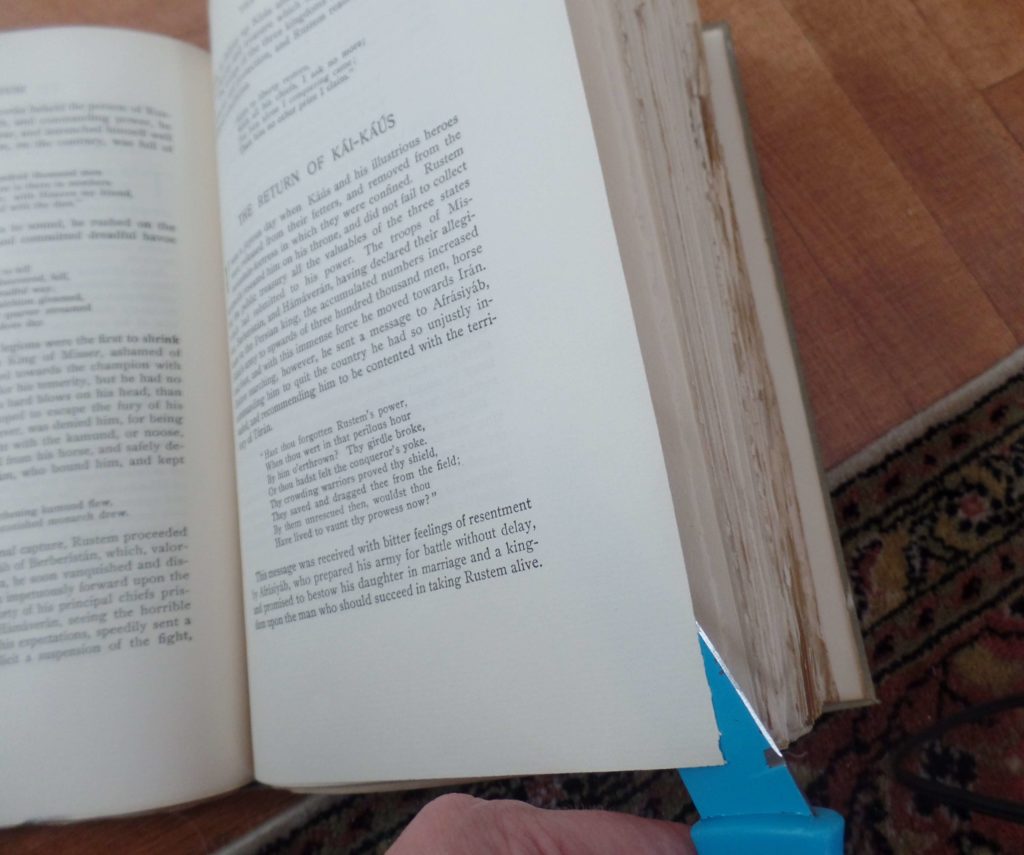

Recently, I noticed on my bookshelf this copy of The Shah Nameh, printed in 1900, and started to read through it. The edging was uneven, and uncut pages hid portions about every 10 to 15 pages. So I read it with a sharp knife to reveal these pages. As I read, I realized my eyes just revealed a page [in this book] hidden for 120 years, which no one has opened.

Gifted Shah Nameh

The man who gave me this one volume from his massive set was a pastor in upstate New York. He is a lover of reading and books. As we talked about missions and church, the conversation led to the subject of Persians in the Bible. In light of this, he asked me to follow him upstairs to his hidden library. He appreciated the Classics but did not have the time to dig into the Persian world. When he enthusiastically invited me into his library world, we saw piles and bundles of assorted books – only making sense to him. He pointed out the classics stacked like Babel in one corner. I noticed the word Persian Literature on the binding of one of the books which he quickly gifted me. Again the book sat on my bookshelf for 20-plus years, only to be opened at last.

Stories of Love

I unveiled the stories hidden to the eye by these uncut pages – stories of love and bravery. I again read, newly inspired to handle and enjoy some of these Persian stories.

Gureng’s daughter smitten love for Jemshid (spelling of Jamshid back in 1900). The pages are filled with her commitment and selflessness as she says:

“How long hath sleep forsaken me? how long hath my fond heart been kept awake by love? Hope still upheld me – give me one kind look, and I will sacrifice my life for thee; Come, take my life, for it is thine for ever.” [1]The World’s Greatest Classics, Persian Literature, Vol. 1. New York: Colonial Press, 1900. Firdusi. The Shah Nameh, trans. James Atkinson, 22.

Resentment and Peace

Irij’s sentiments:

“I feel no resentment, I seek not for strife, I wish not for thrones and the glories of life; What is glory to man? – an illusion, a cheat; What did it for Jemshid, the world at his feet? When I go to my brothers their anger may cease, Though vengeance were fitter than offers of peace.”[2]The World’s Greatest Classics, Persian Literature, Vol. 1. New York: Colonial Press, 1900. Firdusi. The Shah Nameh, trans. James Atkinson, 39.

Atkinson’s Translation

What did James Atkinson think when he translated this massive poem? He worked in Calcutta for the British government, dabbling in a few languages. However, his enjoyment of Persian tempted him to translate the enormous work. As a result, his attempted prose in poetry becomes quite readable.

Like the English Bible, Atkinson translated names phonetically and intermixed commentary with poetry. He retains the names with Persian pronunciation, which honors the book as The Shah Nameh, not the King’s letter.[3]Doris Alexander in Creating Literature out of Life, 60

Ferdowsi’s Persian

The reader, as if sitting alongside Ferdowsi in Persia, when hearing the transliterated names in English, receives a fresh meaning. His rendition enables one to get one’s feet wet before fully diving into Persian, a language flowing with emotion. Zal meeting Rudabeh privately for the first time gives the emotional sense:

At length the warrior rose, and thus addressed her: “It becomes not us to be forgetful of the path of prudence, though love would dictate a more ardent course. How oft has Sam, my father, counselled me, against unseeming thoughts, – unseemly deeds, – always to chose the right, and shun the wrong. How will he burn with anger when he hears this new adventure; how will Minuchihr indignantly reproach me for this dream!” [4]The World’s Greatest Classics, Persian Literature, Vol. 1. New York: Colonial Press, 1900. Firdusi. The Shah Nameh, trans. James Atkinson, 58-59.

Marriage in the Shah Nameh

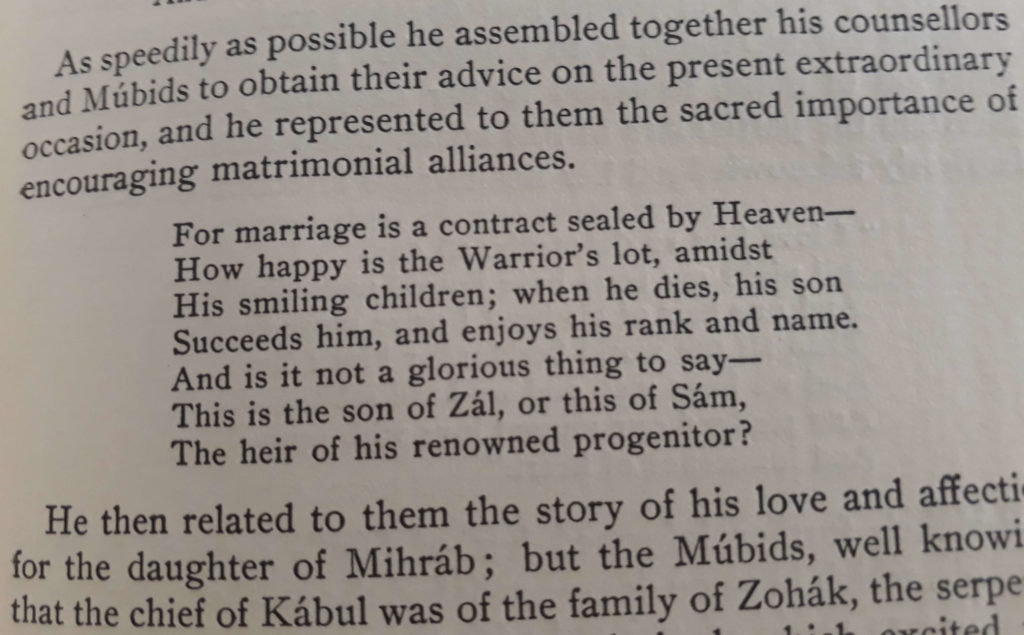

The contractual sense of Islamic marriage shows through in the Shah Nameh when Zal speaks of his coming marriage to the Kabulian prince, Rudabeh: For marriage is a contract sealed by Heaven – How happy is the Warrior’s lot, amidst his smiling children; when he dies, his son succeeds him, and enjoys his rank and name.[5]ibid. 59. Marriage a contract and dictated by their book, which they say came from above for the honor of the man. His position and reputation depend on a good marriage. (For more information on Contract see Searching Below the Surface).

Princess Rudabeh gives the sentimental version when she says:

I love him so devotedly, all day, all night my tears have flowed unceasingly; and one hair of his head I prize more dearly than all the world beside; for him I live.[6]ibid., 60.

Yet, Zal seeks approval from the political situation and security in his social standing of honor – giving allusions to their future son, Rustam.

In light of these musings, I will often cut through #81 and see what other hidden pages inspire.

References

| ↑1 | The World’s Greatest Classics, Persian Literature, Vol. 1. New York: Colonial Press, 1900. Firdusi. The Shah Nameh, trans. James Atkinson, 22. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The World’s Greatest Classics, Persian Literature, Vol. 1. New York: Colonial Press, 1900. Firdusi. The Shah Nameh, trans. James Atkinson, 39. |

| ↑3 | Doris Alexander in Creating Literature out of Life, 60 |

| ↑4 | The World’s Greatest Classics, Persian Literature, Vol. 1. New York: Colonial Press, 1900. Firdusi. The Shah Nameh, trans. James Atkinson, 58-59. |

| ↑5 | ibid. 59. |

| ↑6 | ibid., 60. |

[…] For further Persian studies, check out Cutting the Shah Nameh. […]