- Hidden Crosses in the Dushanbe Archeology Museum

- Hidden Crosses in Khujand Archeology Museum

The National Antiquities Museum in Dushanbe boasts of the sleeping Buddha, excavated in the 1960s from Bokhtar (Ajina Tepe) in the southern region of Tajikistan. Yet, scattered throughout the two-story building are elements of Christian history without any description. The museum displays multiple hidden crosses.

Despite this, the Museum presents a diverse perspective on the history of Central Asia. The region was controlled and influenced by multiple kingdoms like the Kushan, Parthian, and Samanid empires. However, the Christian influence came from the Church of the East, which formed communities throughout Central Asia. They used the Syriac alphabet to write Sogdian, examples of which can be found as far east as China.[1]https://www.academia.edu/57203378/THE_LITURGICAL_LANGUAGE_OF_THE_CHURCH_OF_THE_EAST_IN_CHINA[2]Also Mark Dickens’ write up https://www.academia.edu/398258/Nestorian_Christianity_In_Central_Asia

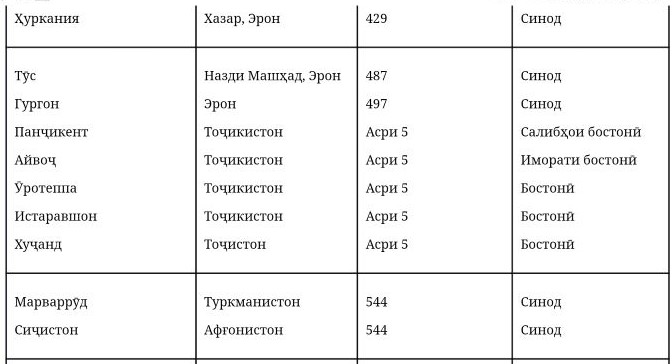

Central Asian Church History

There were many churches in Central Asia, as Persian and church history attests (the list in Tajiki displays below from www.dardidil.com). In light of these facts, what does this Museum reveal when thinking about Christian history? Hidden crosses are Christian elements that the host country underemphasizes either purposely or because the history is not known.

Penjikent Christian Evidence

On the first floor, a pottery sherd displays an example of a red cross outlined in black. The display mistakenly places the cross near items labeled before the birth of Christ. Yet the source is near Sarazm, located five kilometers west of Penjikent (sometimes spelled Panjikent), where Sogdian was spoken. Unfortunately, the historical descriptions of Sarazm in the museum focus on the beginnings of this civilization; there are no comments on when the community ended or when it migrated toward Penjikent (sometimes spelled Panjikent). The small archaeological area dug up on Sarazm focuses on 3000 B.C. to 1500 B.C..[3]https://www.worldheritagesite.org/list/Sarazm Bobojon Ghafurov[4]Ghafurov, Tajiks: Pre-Ancient, Ancient and Medival History, Dushanbe: Irfon, 2020, 601. mentions that this civilization ended near 1500 B.C., so I suspect this cross must have been found near that site since other Christian items came from Penjikent.

This cross and the crosses found on coins in the Osrušana (Ushrusana) hoard present many similarities. These coins depict a Sogdian ruler on one side and often a tiny cross on the other[5]SMIRNOVA, 1981, 32, most likely from Ushrusana’s capital, Bunjikat.

Multiple discoveries and even what appears as a Christian grave site in the Penjikent area (Urtakishlak, Уртакишлок) indicate a strong Christian presence. Barakatullo Ashurov refers to a burial of a young child with a cross and other similar burials which depict Christian influence.[6]Barakatullo Ashurov. Tarsākyā: an analysis of Sogdian Christianity based on Archaeological, Numismatic, Epigraphic and Textual Sources, 2013, 147. He labels the area as Dashti-Urdakon (literally the middle grassland location), which the village of Urta – kishlak meaning middle village in Uzbek, placing this within one-kilometer southeast of Sarazm. Another, Lala-Comneno lists the site one kilometer southeast of Penjikent.))[7]ASHUROV, B. (2019). ‘Sogdian Christianity’: Evidence from architecture and material culture. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 29(1), 163. doi:10.1017/S1356186318000330.[8]Maria Adelaide Lala Comneno, Nestorianism in Central Asia during the First Millennium:

Archaeological Evidence, 1997, 37. Despite a few kilometers difference, either location places this cross-shard near Penjikent. The de-emphasis on this shard makes it one of the key hidden crosses in the museum.

Penjikent Ossuary

This ossuary (below) from Penjikent displays several crosses with flower-shaped endings. The size of the ossuary indicates the deceased died young. The Afrasiab settlement in section of the Samarkand Museum displays adult ossuaries similar to this. Just like these, the three-leaf cross sits within a partial oval circle. In some locations, these vessels held the bones of those who died.

The display area in the Dushanbe museum says this ossuary came from Penjikent, but there are no details on the location of the clay vessel. Similar to this item, the excavations of 2019 in Penjikent found an ostracon (pottery sherd) that exhibited Syriac Christian writing.[9]https://voicesoncentralasia.org/panjikent-the-central-asian-pompeii-an-interview-with-pavel-lurje/ Previously from this same area, Archaeologists found a shattered pottery ostrakon that quotes three verses of Psalm one and six verses of Psalm two in Syriac.[10]A.V. Paykova “The Syrian Ostracon from Panjikant,” Le Muséon 92/1-2, 1979, pp. 159-69 and B.I. Marshak refer to this finding. This inscription sherd comes from the late 8th century.

Mysterious Hidden Crosses

I love this oil lamp, which depicts multiple crosses. It is a definite gem of the hidden crosses in the museum. The long shape extends a bit farther than a Byzantine lamp; it came from the Bundjikat (Bunjikat, Бунҷикат) site in Shahristan in the Ferghana valley. This city thrived from the 5th to the 9th century. The Archeological Museum of Khojent displays similar Christian objects from this site, giving us a fuller picture of Christian influence in the area.

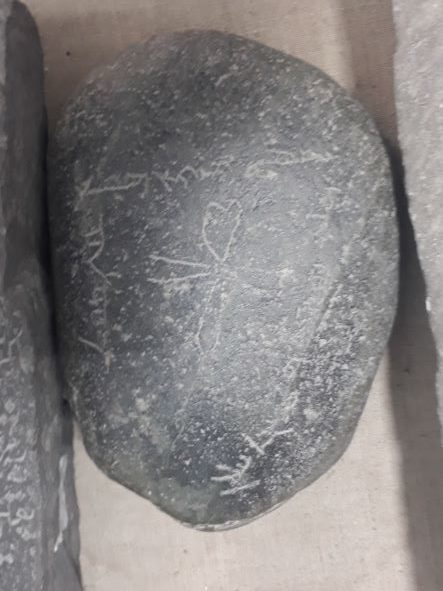

This gravestone with pearled-cross and Syriac writing most likely comes from north of Tajikistan. Seeing this stone a few years ago in the Museum, I wrote Dr. Mark Dickens to ascertain where it came from. The Tashkent Museum displays similar stones that Dr. Dickens has written about.[11]Mark Dickens writes about similar stones in Echoes of a Forgotten Presence: Reconstructing the History of the Church of the East, 253.

Cross-shaped Molds

The four objects in the picture on the right displays the hidden nature of Christianity in the Museum. This display on the second floor gives no signage. The case gives no indication of source, or any other information. The third item from the top is a mold to form crosses. Mark Dickens said, “Many of these crosses were locally made, as evidenced by the discovery of casting moulds in Merv and Rabinjan, between Bukhara and Samarqand[12]Rott 2006; Savchenko and Dickens 2009: 131–2, 297, 299; Savchenko 2010: 77

The other objects may come from an entrance way. The spiral images at the top and bottom could represent God’s eternality, a symbol found in many Byzantine church buildings. The other clay symbol (second for the top) has a six-point hexagon in the center, possibly a solar mark found.

In a December 2022 visit, another mould was placed alongside the other, creating more curiosity with this addition (photo taken by Payrav Gardiev). These hidden crosses give testimony in this Dushanbe museum.

Other Hidden Cross Items

The pics of a door handle (left) and cross jewelry (right) represent how these Central Asian believers showed their faith. In 2007, when I first visited the Museum, these crosses were on display, but I did not see the jewelry pieces on my recent visit in 2022. The Four petal Almond Rosette has multiple meanings for many religions. Still, these items were widely used in the Christian Semirechye region (present-day southeastern Kazakhstan and northeastern Kyrgyzstan).

Charles Anthony Stewart said, “Likewise, I suggest that the Christian almond-rosette was a symbol of a symbol; that is, the flower symbolized the life-giving cross, which itself was a symbol of God’s sacrificial love for humanity. As such, the rosette form was also paradoxical, because it functioned as both a beautiful ornament as well as a simple sign of a complex belief system. Moreover, because it is a reversible image, Christians could use it to disguise their faith during times of persecution, while openly expressing their belief.”[13]Charles Anthony Stewart. The Four-Petal Almond Rosette in Central Asia, Bulletin of IICAS, 2020 82.

Christian Structures

Barakatullo Ashurov says that historical researchers have found only six Christian structures (monasteries or churches) so far in all of Central Asia.[14]http://www.exploration-eurasia.com/pictures/Urgusogdian_christianity_evidence_from_architecture_and_material_culture.pdf These structures are located in Merv (Turkmenistan), Termez (Uzbekistan), Urgut (Uzbekistan) and Aq-Beshim (Kyrgyzstan). The others include the excavated churches in Central Asia, including Turfan (Xinjiang, China) and Olon Süme-in Tor (Inner Mongolia, China). Besides church structures, some locations show forth caves used as monasteries, like the one south of Kabodian in Tajikistan, on the banks of the Amu Darya.[15]https://rsaa.org.uk/blog/in-search-of-ancient-christianity-the-nestorian-caves-of-tajikistan/

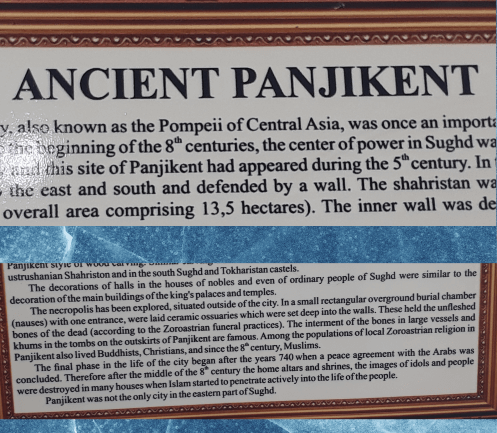

The one place where the Museum credits Christianity is the write-up on Panjikent. On the wall plaque, they acknowledge that many religions existed in this ancient location, listing Christianity.

Yet, throughout this museum, a testimony to the past influence of the Church of the East survives. The hidden crosses are numerous. When visiting the Dushanbe Antiquities Museum, one can notice the many objects showing additional evidence of early Christian impact in the area.

To follow:

For further reading, please see the following:

Ashurov, Barakatullo. Sogdian Christianity Evidence. 2018.

Ashurov, Barakatullo. (2013) Tarsākyā: an analysis of Sogdian Christianity based on

archaeological, numismatic, epigraphic and textual sources. Ph.D. Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18057. (Without a doubt a worthy read, presenting many objects which explore the multiple objects that reveal Christianity’s influence in Central Asia.)

Dickens, Mark. Echoes of a Forgotten Presence: Reconstructing the History of the Church of the East in Central Asia (2020). (Anything written by this author is full of scholarly proof.)

Jon, Nakhati. Худо ҷӯёи Тоҷикон аст

References

| ↑1 | https://www.academia.edu/57203378/THE_LITURGICAL_LANGUAGE_OF_THE_CHURCH_OF_THE_EAST_IN_CHINA |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Also Mark Dickens’ write up https://www.academia.edu/398258/Nestorian_Christianity_In_Central_Asia |

| ↑3 | https://www.worldheritagesite.org/list/Sarazm |

| ↑4 | Ghafurov, Tajiks: Pre-Ancient, Ancient and Medival History, Dushanbe: Irfon, 2020, 601. |

| ↑5 | SMIRNOVA, 1981, 32 |

| ↑6 | Barakatullo Ashurov. Tarsākyā: an analysis of Sogdian Christianity based on Archaeological, Numismatic, Epigraphic and Textual Sources, 2013, 147. |

| ↑7 | ASHUROV, B. (2019). ‘Sogdian Christianity’: Evidence from architecture and material culture. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 29(1), 163. doi:10.1017/S1356186318000330. |

| ↑8 | Maria Adelaide Lala Comneno, Nestorianism in Central Asia during the First Millennium: Archaeological Evidence, 1997, 37. |

| ↑9 | https://voicesoncentralasia.org/panjikent-the-central-asian-pompeii-an-interview-with-pavel-lurje/ |

| ↑10 | A.V. Paykova “The Syrian Ostracon from Panjikant,” Le Muséon 92/1-2, 1979, pp. 159-69 and B.I. Marshak refer to this finding. |

| ↑11 | Mark Dickens writes about similar stones in Echoes of a Forgotten Presence: Reconstructing the History of the Church of the East, 253. |

| ↑12 | Rott 2006; Savchenko and Dickens 2009: 131–2, 297, 299; Savchenko 2010: 77 |

| ↑13 | Charles Anthony Stewart. The Four-Petal Almond Rosette in Central Asia, Bulletin of IICAS, 2020 82. |

| ↑14 | http://www.exploration-eurasia.com/pictures/Urgusogdian_christianity_evidence_from_architecture_and_material_culture.pdf |

| ↑15 | https://rsaa.org.uk/blog/in-search-of-ancient-christianity-the-nestorian-caves-of-tajikistan/ |

Leave a Reply